THAM LUANG CAVE RESCUE

The story began when Peerapat "Night" Sompiangjia decided to spend his birthday with the rest of the team- the Wild Boars and their assistant coach Ekkapol" Ake" Chantawong. When their practice session ended, they decided to race for the forested hills on their bicycles.

The hills were slippery and wet due to the frequent rain, but it didn't stop the boys from continuing their journey. They loved to explore the different parts of Mae Sai, most notably its mountain ranges and their destination for that day was The Tham Luang Cave, and this is where the real nightmare began.

It was quite unexpected what happened to the boys because it wasn’t their first time to go inside and explore the vast network of passages inside Tham Luang cave. This was one of their favorite outdoor activities and in fact the cave wasn’t a stranger to them. The boys were aged from 11-16 and with them was their 25-year old coach. They decided to take a fun trip to the caves after their football practice and wasn’t really expecting they will be staying trapped inside the cave complex for 2 weeks going hungry and cold in the process.

It is not recommended to explore caves during the rainy season, and it is entirely unsafe to go down on caves if it rained just recently. Most explorers and travelers have this basic knowledge, but since the boys did not have a proper guide, they went ahead and entered the cave.

The group was not exactly unfamiliar with the Tham Luang Cave. They had already taken several trips inside the cave before as a part of their initiation rites.

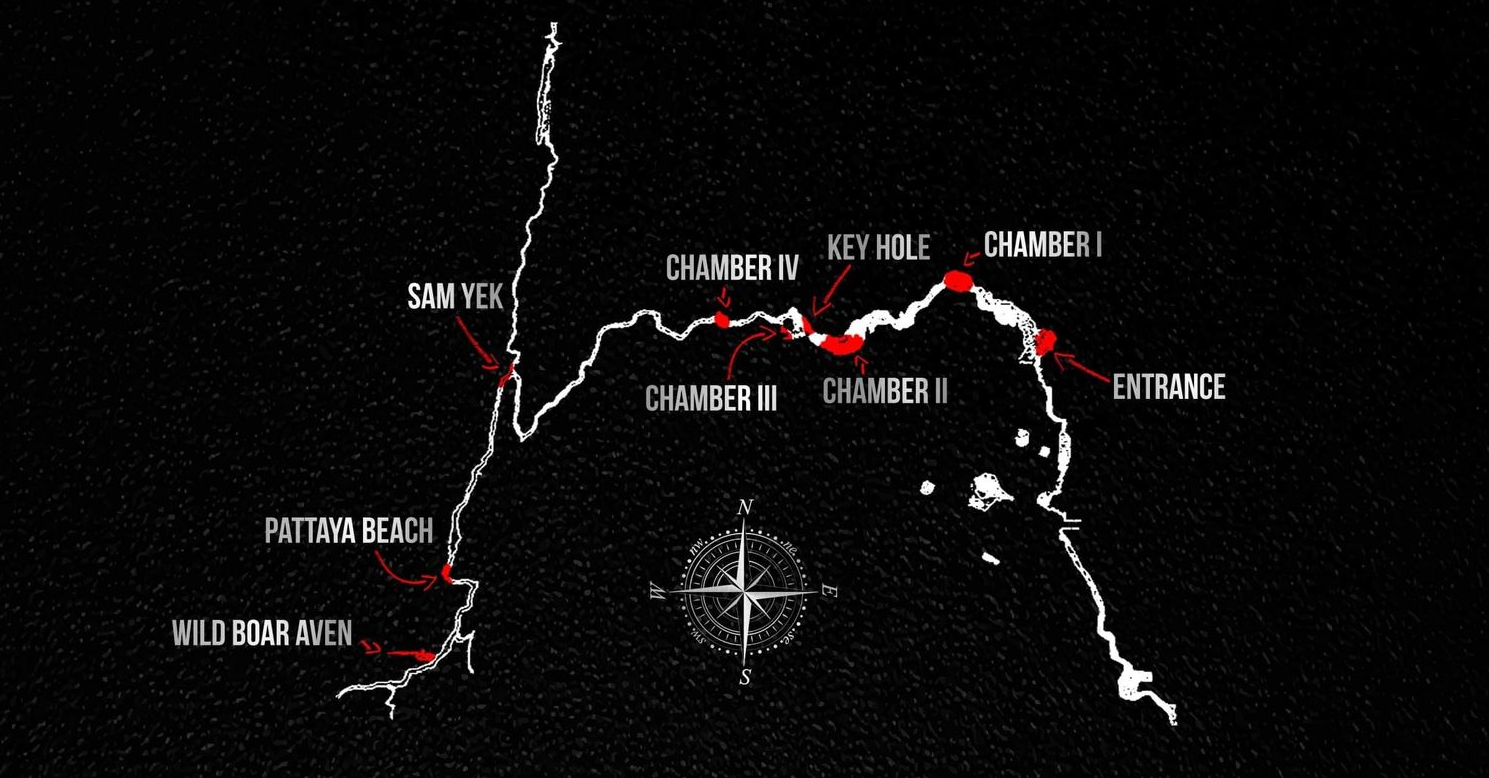

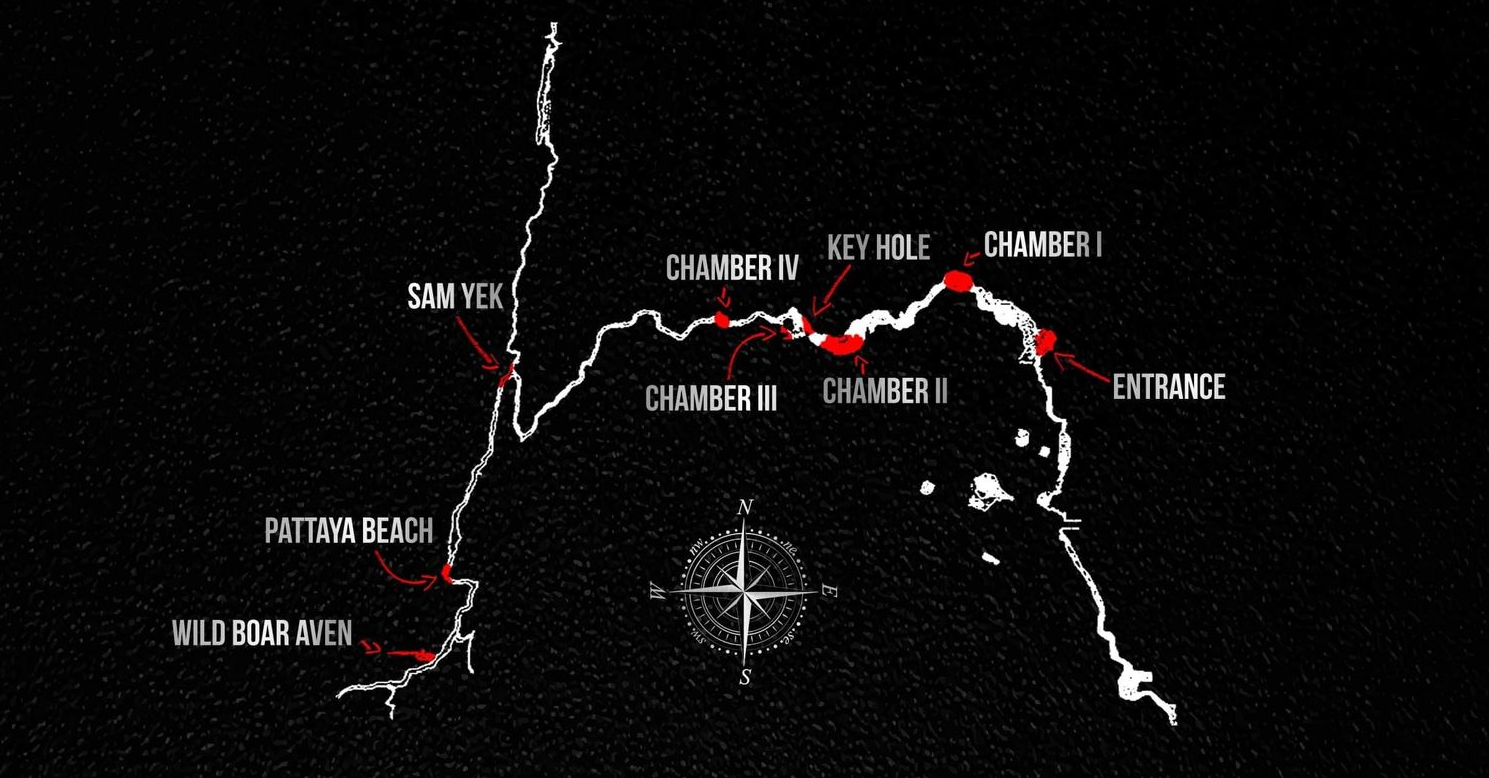

The mouth of the cave was a well worn course and it was even cemented in some parts, and past that, the Tham Luang narrows before starting again into a sequence of chambers. 1.6 kilometers in, when the cave constricts to a mud-floored passage, it's nonetheless high enough and wide enough for a grown guy to crawl through.

The Wild Boars group and their coach had no issue getting inside. They crawled through a couple of choke points to the open spaces and they expected no difficulty getting back out either. But the group never anticipated the heavy monsoon rains which poured and poured. The rains weren't scheduled for another week like last year’s but they came early this year and the cave began to flood. The team brought no meals or critical caving gear because they were there just on a short excursion. They only planned to stay for possibly an hour, then get back out and celebrate the birthday of “Night” but that was not to be the case.

The rain started and continued pouring down. Flood water started to rise and Coach Ek tried to swim out, waiting for the boys to follow but they couldn’t. More water came, and the Wild Boars retreated farther, scrambling up to a chamber with a sandy patch known as Pattaya beach. Then they went down once and up once more, subsequently reaching a better spot beyond. They settled on a steep slope above the muddy flood waters.

The boys didn't come home, and their parents began to worry. They decided to call and send messages to the head coach and other parents. The coach was able to reach the only member that didn't go with the team. They went to the cave, and parents went as well, and there they found bicycles and several of the boys’ items at the mouth of the cave. The Wild Boars were trapped.

And then the first miracle occurred. Near the city of Chiang Rai, there was a man who knew the innards of Tham Luang like no one else. Vern Unsworth is a 63-year-old British cave expert hailing from Lancashire who had made Chiang Rai his home for over half a decade.

Unsworth was readying his gear to check the water levels in the cave when he got a call very early in the morning of June 24. Locals who knew Unsworth decided to call him when they discovered the trapped boys in the cave, and Vern immediately went to work. As an expert, he knew the importance and risks of going into the cave. He first had to look for the Wild Boars, which was crucial considering the enormous size of the cave, and the time pressure involved as more rains were expected to come soon.

The second crucial thing that Unsworth was most certain of is that expert cave divers would be required, and that normal divers were not sufficiently equipped for the search and rescue mission ahead. Cave diving is very specialized and wildly risky, so much so that it is not even covered in most naval dive education courses. The Thai navy seals, who were called in about the same time as Vern, also tried their very best to help out with the rescue. Although they are all well trained in their own right, it was still a great challenge for them to find the boys and rescue them out of the cave.

Unsworth, being a cave expert himself, knew of divers who were experts in their field, and he gave the government 3 names: Rick Stanton, John Volanthen, and Robert Harper, all of whom are members of the British Cave Rescue Council. Unsworth told the Thais to get in touch with the three through the British embassy. They arrived at the cave's rescue site at 7:30 p.m. on Wednesday, June 27.

Vern’s quick thinking, bullish character and determination to bring the boys out to safety played an essential role and paved the way to one of the most nerve-wracking but successful rescue operations in history.

The rain somehow stopped on Sunday, however poured heavily again on Monday and Tuesday. Water started pouring from the sky and into the streams and down through the valleys. Deep in Tham Luang, the Wild Boars had no food, and the flood waters were muddy and undrinkable.

Coach Ek pointed to the stalactites growing from the ceiling, surprisingly natural water dripping off them and they were able to hydrate themselves with it. The boys, determined to dig their way out of the cave used rocks to scrape out a passage at the top. Their efforts were futile.

Coach Ek had been a practicing monk for ten years so he knew how to meditate. With this knowledge, he taught the boys to breathe slowly and purposefully, to clear their minds, to take away themselves mentally and emotionally from their physical state. The meditation helped to slow down the heart rate of the boys, metabolism downshifted, and panic was quelled for the time being. It helped calm down the group which was very important in keeping them alive.

Outside, it still continued to rain heavily. However, rescuers and volunteers continued to arrive to try and lend a hand and do whatever they could to help out for the boys and the rescue teams. The search and rescue teams knew they had to get as much water out of the cave so they diverted the water from the cave to a huge rice paddy to help reduce the flood waters entering into the cave.

It must have been terrifying for the boys and more so for their coach who was the only adult and therefore responsible for the 12 kids. Highly skilled Thai Navy seals were already called in to help with the rescue as early as Day 2 but they couldn’t immediately locate the group as mother nature also didn’t make it easy. It was monsoon season and rising waters inside the cave hampered the search inside it for the lost boys and their coach.

Divers continued to dive and laid out ropes to guide them in and out of the cave. Strong currents somehow stopped them at the T-junction but they still tried to go deeper in the cave with every journey.

On July 2, the ninth day of the operation, British divers, Stanton and Volanthen made it all the way to Pattaya beach. They surfaced there but did not find the group. They nonetheless had a few ropes left and so they continued on.

Thirteen humans restrained in a small space with limited airflow will eventually create a stink. The 2 British divers followed the smell and found the boys and their coach, all 13 of them standing in an elevated steep mud slope 2.4 kilometers from the cave’s entrance. The divers stayed with the boys for a while and tried to boost morale and promised to return with food and water. Stanton and Volanthen had found the group and everyone was quite okay but this was just the beginning. Now the next thing to strategize was how to get the group safely out from where they were trapped?

In the beginning, the authorities discussed all possible options to rescue the Wild Boars out from the Tham Luang. One of which was to wait until the monsoon season ended and the water level goes down low enough for the boys to just walk out of the cave. This possibly could have been November or perhaps even December. But the logistics and the incoming monsoon season with more rains will make this option quite fatal. If they were to push through with this plan, Coach Ek and the boys will have to be fed for 5 months. Thirteen humans eating three times a day will need a lot of food to be delivered to them constantly. Also, the fact that the oxygen level was starting to drop inside the cave made it a non viable option too. Time was really running out.

While the rescue mission was ongoing, a former Thai Navy SEAL named Saman Kunan died while delivering spare oxygen tanks within the cave. His own tank ran out and his dive buddy tried to revive him but he never regained consciousness. Other SEAL divers got him out and was declared dead at a health facility. It was a devastating news but it only went on to show how dangerous the rescue mission was going to be. This also raised doubts if the plan can be executed successfully.

They tried to look for other angles to extract the boys and even thought of drilling through a couple of thousand feet of rock but this would require heavy equipment and might take too much time. But nobody was willing to give up, volunteers crawled over the mountain, looking for possible openings. The surface team lead by Unsworth and Rob Harper searched every nook and cranny hoping to find any possible entry/exit point on top of the mountain. More people looked for alternate openings such as CMRCA and even those responsible for pumping out water like Thanet Natisri and team. Even climbers from Koh Libong Island roped up the faces of the mountain, looking for hidden openings. They discovered none.

None of the earlier plans seem to be feasible at that moment so they were left to the last alternative: swimming the boys and their coach out of the cave through several chambers that were already underwater. Although this method had the advantages of being faster, it was also quite difficult since none of the boys nor coach Ek knew how to dive. Even though they could learn the fundamentals, cave diving is not similar to an exercise run in a lodge swimming pool and this could prove fatally dangerous to everyone involved.

A weakened individual submerged in disorienting darkness and breathing unnaturally through a regulator will most probably feel panic and considering the lengthy stretches of the cave, the group would have to go through, an instance of panic might be a factor in a life or death situation.

The Wild Boars still were not rescued and time was running out so they decided to go with swimming the boys out through the flooded cave chambers. The first step was that the rescuers delivered full-face respirators to the boys and their coach. Rather than sticking a regulator in every boy's mouth, they were given full face masks that included the whole of the face from their chins to their foreheads. This lessened the possibility of the boys and their coach losing the regulator when they’re being taken out from the cave.

On July 7, Australian cave diving anesthesiologist Harris, swam to where the Wild Boars were holed up so that he could evaluate them. D-Day was drawing close. The subsequent morning, a group of divers, along with Harris, Stanton, and Volanthen, made their way to the muddy area where the stranded Wild Boars and their coach were.

There were discussions about who to rescue first but during that time, the first boy who volunteered was chosen. He was strapped into an improvised harness, with which he could be tethered to a diver, then bundled into a buoyancy jacket to maintain his neutrality in the water. Too heavy, and he'd be held above the rocks on the lowest; too light, and he could bump in opposition to the cliffs above, dislodge his mask, and drown.

After that was all done, the boy was sedated. It was a quick-acting medicine that put him in a state close to slumber, but the drug wears off in about 45 minutes so the other cave rescuers were given a crash course in re-administering it if they needed more time in getting the boys safely out of the cave.

They slipped underneath the water, the boy as if a package, still and quiet. In dry spots, or at the areas that weren’t completely flooded, the alternative rescuers brought him from chamber to chamber. In places where the flood waters were chin-deep, high lines were installed by CMRCA to pulley out the kids to the mouth of the cave while secured in a stretcher.

In the afternoon of July 8, more than 4 hours after the divers left the ledge, the first Wild Boar was brought to the mouth of the cave, alive and relatively healthy. He was delivered straight into an ambulance, pushed to a helicopter, after which flown to a health center in Chiang Rai to be weaned, returned to a proper diet and monitored for respiratory contamination as well as for signs of psychological distress.

The next boy was out forty-five minutes after the first, then the third and fourth in similar duration. And that was it for the day. Air tanks needed to be restocked, divers had to rest. But the rescue efforts continued deep in the cave with people shoveling from the passageways that were not flooded, clearing and smoothing the direction.

On July 9, four more boys were pulled out and pushed and floated and carried out from the cave. The rescuers were practiced now. It took less time to get a boy thru 2.4 kilometers of floodwater, rock and mud.

At the very last day, the remaining five got out. After which, the waters began rising once more. One of the massive pumps that had been draining the cave failed, but luckily all of the boys had made it out of the cave as well.

Eight days after the successful rescue mission, the Wild Boars were released from the hospital. They left the medical institution in good condition and their families were glad to have them back.